Speech-language pathology intervention for young offenders

Swain, N. R. (2018). The University of Melbourne.

PhD Research. Supervised by A/Prof Tricia Eadie and Prof Pamela Snow.

Send me an email to request a copy of PhD Thesis

Background

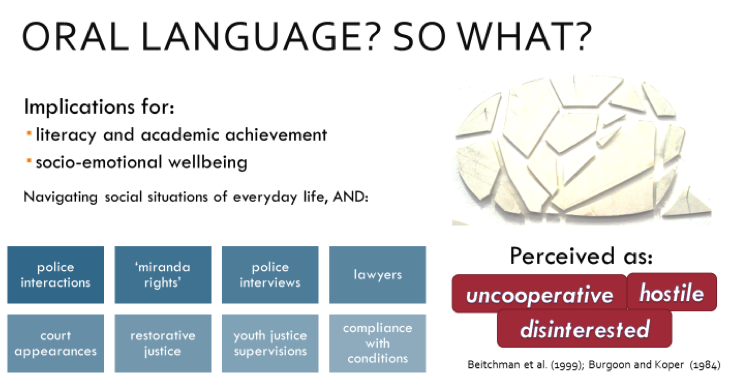

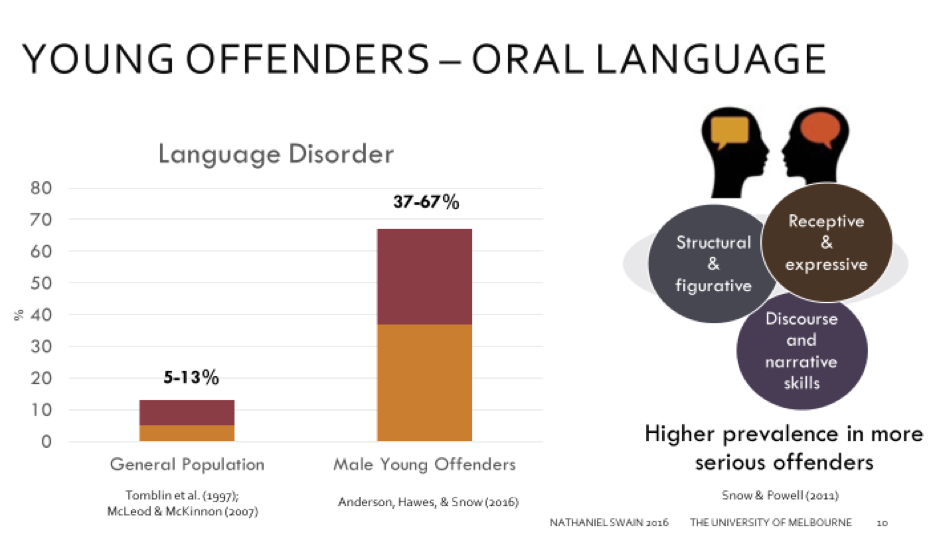

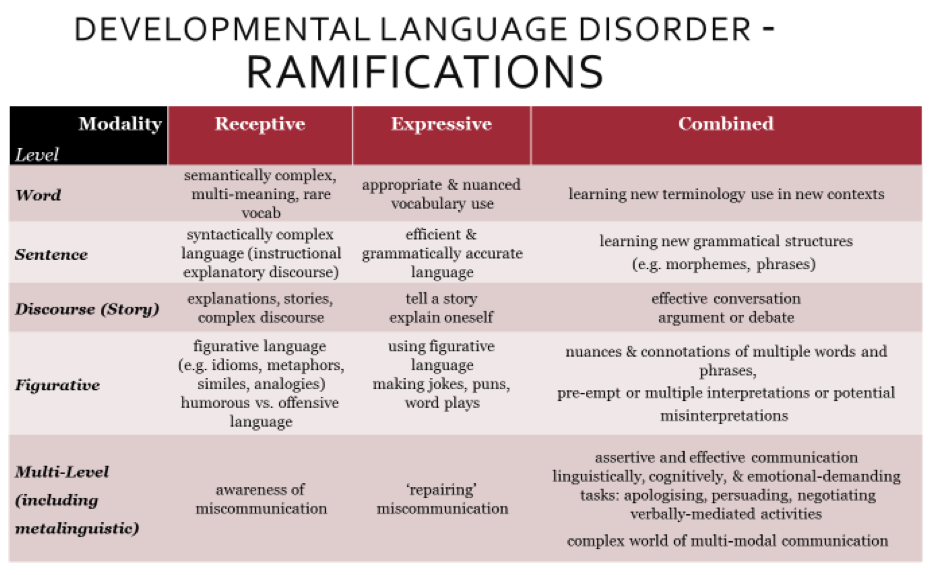

Young people in youth justice are a vulnerable and marginalised group, who are at high risk of speech, language, and communication needs (SLCN). Fifty to sixty percent of male young offenders have developmental language disorder. This means they struggle to understand or express themselves with spoken language, as well as other young people their age. In terms of their education, speech, language, and communication needs can affect students’ ability to:

· understand and participate in classes

· appropriately express and regulate their emotions

· learn the basics of literacy and numeracy.

Research Aims

This PhD research had three main aims:

I) assessing the language, social cognition, and executive functioning skills of young offenders;

II) investigating the effectiveness of Speech-Language Pathology (SLP) intervention for young offenders; and

III) describing the feasibility of providing an SLP service within a youth justice centre.

Study 1: Assessment

METHODS: This was a cross-sectional study of twenty-seven young offenders, each with no reported history of traumatic brain injury or psychotic illness, and all having English as their primary language. Standardised assessments of language, social cognition, and executive functioning were administered, together with self- and teacher-rated measures.

Social cognition refers to the awareness of subtle social behavioural cues, and is important for building and maintaining social exchanges and relationships. Executive functioning is an umbrella term encompassing a range of cognitive skills. People with poor executive functioning have difficulties with working memory, planning, inhibition, sustaining attention, and/or mental flexibility – and may have behavioural problems as a result.

I compared participants’ performance on language, social cognition, and executive functioning with available population norms, and conducted correlation and regression analyses.

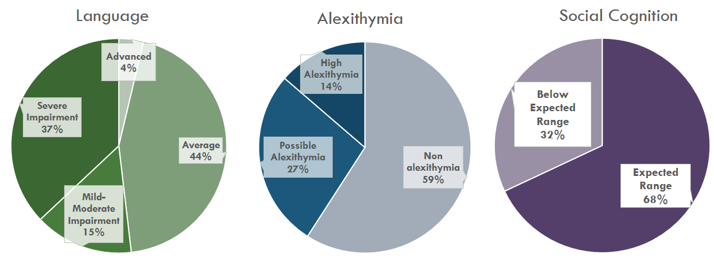

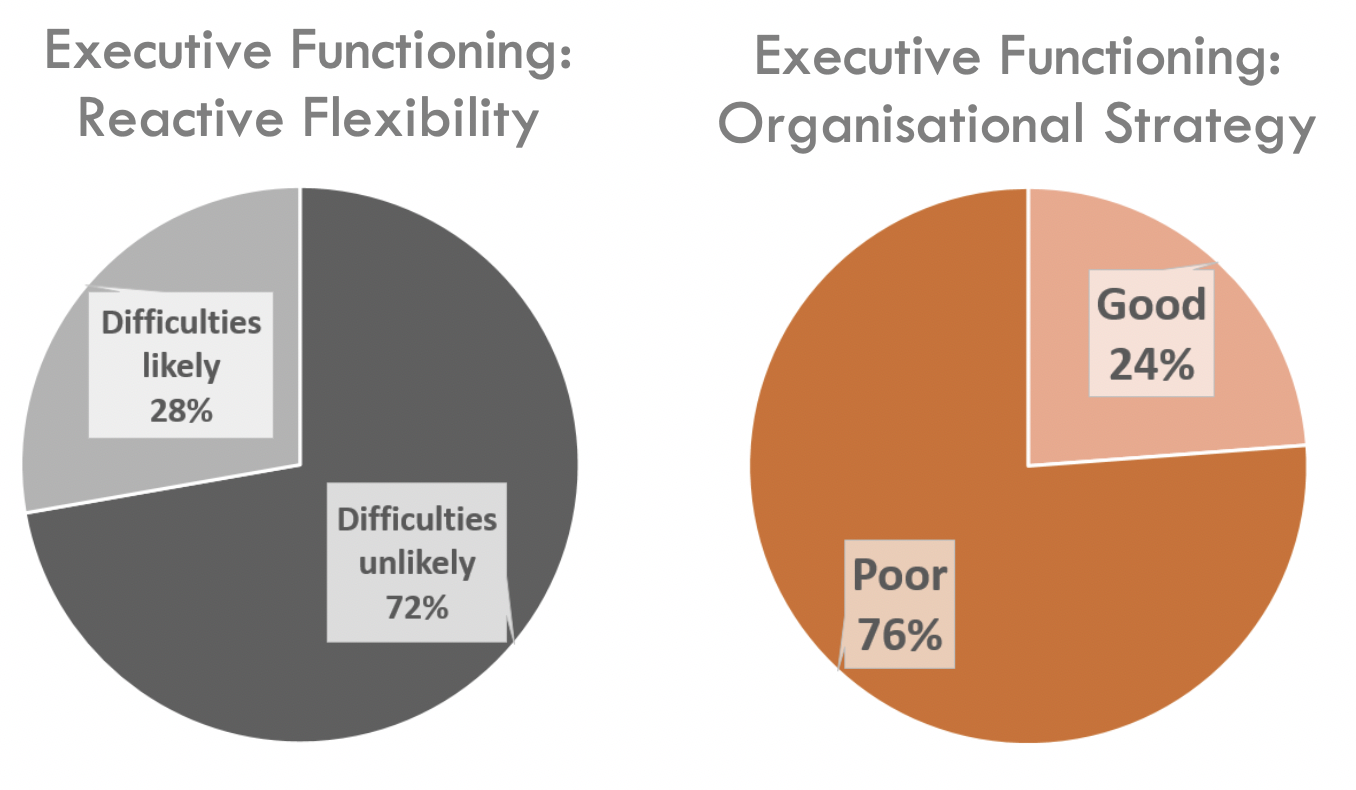

KEY RESULTS: Half of participants had language disorder (52%). This included 15% with mild-moderate difficulties, and more than a third of participants with severe language disorder (37%). One third had social cognition deficits, and deficits in subskills of executive functioning ranged from one to three quarters of participants (see figures below). Alexithymia (difficulty identifying and attaching verbal labels to one’s emotions) was also common in the sample, with 41% likely to be affected by this phenomenon.

Regression analyses indicated that social cognition and executive functioning significantly predicted variability in oral language, suggesting that language skills are central to the difficulties in social cognition and executive functioning observed in young offenders. This provides further rationale for the need to conduct language assessments with clients in youth justice, as such assessments may contribute to understanding the emotional and behavioural difficulties in this group.

Study 2: Intervention Cases

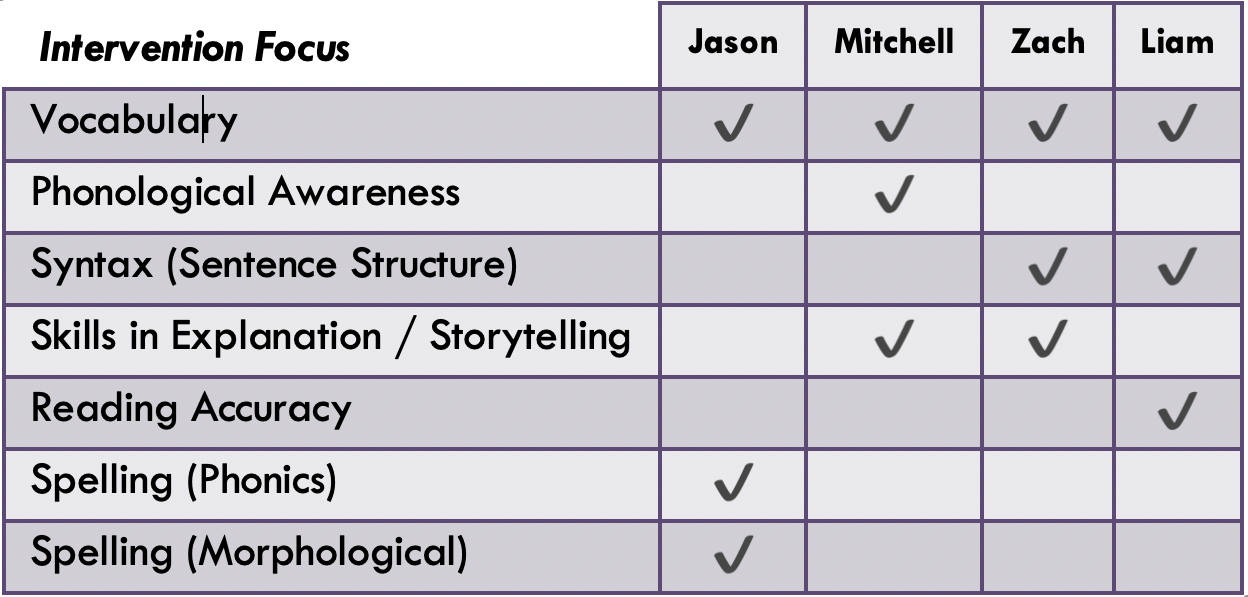

METHODS: The language intervention trial involved four single case studies. I aimed to test the effectiveness of one-to-one language intervention to improve the communication skills of a subsample of individuals from Study 1. I worked individually with four students on their own language and literacy goals, and I measured their progress throughout the baseline, intervention, and maintenance phases.

KEY RESULTS: There were medium-large improvements in the targeted communication skills. The vast majority of these were statistically significant. Positive results were also evident in comparisons of pre- and post-measures on standardised language subtests, and on ratings of communication by teachers. The participants reported positive experiences of taking part in the intervention, and noticed improvements in their communication skills. For those participants who could be followed up, gains in language skills were largely maintained at one month post-intervention. This provides the most rigorous evidence to date that SLP intervention is effective and worthwhile with young offenders.

Study 3: Feasibility

METHODS: In the final study I aimed to understand the opportunities and challenges of implementing speech-language pathology in the youth justice setting. An independently-facilitated one-hour focus group with the facility’s education staff was conducted at the end of the study. Written transcripts of the focus group were analysed to identify key themes.

KEY RESULTS: The feedback from Parkville College staff in the focus group was overwhelmingly positive. Informal feedback from DHHS and Youth Health and Rehabilitation Service (YHaRS) staff was also positive. Some example quotes from the teacher focus group are included below:

I JUST THINK THE DETAIL OF WHAT … SPEECH PATHOLOGISTS KNOW ABOUT LANGUAGE AND LITERACY MOST OF OUR LITERACY TEACHERS WOULDN'T HAVE THAT KNOWLEDGE

- Literacy Teacher

I THINK IT CONTRIBUTES TO ALMOST EVERY VERSION OF … SUCCESS BECAUSE WHEN A STUDENT … UNDERSTANDS WHAT’S SORT OF HAPPENING THEN THEY TURN UP NATURALLY MORE CALM … AND THEY FEEL LIKE THEY HAVE MORE CONTROL

- Numeracy Teacher

I FOUND IT REALLY HELPFUL … [THE SLP] RUNNING THROUGH A REPORT WITH US … THEN GIVING US STRATEGIES … THEN LETTING US RUN A DEMO OF IT, THEN HAVING CONVERSATIONS ABOUT WHAT DID OR DIDN'T WORK. IT'S INCREDIBLE THAT SORT OF ONGOING SUPPORT.

- Literacy Teacher

HIS WORK WENT BEYOND THE CLASSROOM … AND INTO THE COMMUNITY

- Leading Teacher

The key opportunities of for speech-language pathology services in youth justice are summarised below:

Communication awareness training, including recognising potential signs and reasons to refer to SLP

Communication strategy training from SLPs to optimise communication with clients, for education, health, and youth justice staff

Comprehensive, reliable, and person-centred assessment data and reports

Direct 1:1 SLP intervention services to develop clients’ language and literacy skills

Collaboration with SLPs to create communication accessible resources for education, health, and also youth justice purposes

Collaboration between teachers and SLPs to design language and literacy intervention strategies

Liaising with community SLPs and other professionals to coordinate the continuity of interventions and support plans post-release

Some potential challenges as well as key facilitators, were identified in this study, including:

FACILITATORS

open communication, modelling, and collaboration with teaching staff

importance of building strong relationships with students and staff

benefits of integrating student goals across teaching, youth justice, and health services

CHALLENGES

difficulty scheduling additional sessions within busy student schedules

disruptions and cancellations

difficulty collaborating with health and youth justice to coordinate assessments and interventions

Conclusions

Overall this doctoral research indicates that there are immense opportunities for effective and responsive SLP services in youth justice. Speech-language pathologists can play a key role in youth justice education, including Speech, Language and Communication assessment, intervention, and collaboration with other professionals. This research provided evidence that investing in speech-language pathology could have significant benefits for the young people in contact with youth justice, as well as the other staff working in this sector.

PhD Supervisors

Professor Pamela Snow

La Trobe University

Associate Professor Patricia Eadie

The University of Melbourne

Sincere thanks and appreciation go to

National Health and Medical Research Council

Parkville Youth Justice Precinct

Parkville College staff and students

Dr Nathaniel Swain (2018)

PhD Research. Link to PhD thesis here

Send me an email to request a copy of PhD Thesis